British troops burn White House in 1814; US troops occupy Mexico City in 1847; lessons learned transform US military

- Details

- Published on Friday, 26 October 2012 13:11

- Written by Allyn Hunt

Canada’s government of Prime Minister Stephen Harper will spend 28 million dollars over three years to call what many Canadians term “surprising attention” to the bicentennial of the 1812 war between a young United States and the British Empire. That war was carried out primarily in Britain’s “North American northern frontier” as it is identified by Jim Guy, professor emeritus of political science and international law at Cape Breton University. (Note for non-Canadian readers: The word Canada comes from the Iroquois word “Kanata,” meaning “village.” A Frenchman, Jacques Cartier, transcribed the word as “Canada,” applied first to the village of Stadacona, then to the whole region of New France. After the British conquest of New France, the colony was renamed the Province of Quebec. Following the American revolution, New France was split into two parts, Upper and Lower Canada, often being collectively, but not officially, known as “the Canadas.” The national title “Canada,” was decided on July 1, 1867, at a conference in London, in which 17 other names were offered, but Canada was unanimously adopted.)

American roots of Porfirio Diaz’s dictatorship began with the looting of the border region; it ended with a rebel victory at Ciudad Juarez

- Details

- Published on Friday, 19 October 2012 14:42

- Written by Allyn Hunt

On November 21, 1877, General Porfirio Diaz, military hero of Mexico’s liberals, entered Mexico City after opposing one of the nation’s great liberal presidents, Benito Juarez (primarily out of pique), and then (out of political opportunism) Juarez’s much disliked, much less liberal successor, Sebastian Lerdo de Tejado. Diaz immediately called for a new election, flourishing his political (and soon to become ironic) banner: “Effective Suffrage. No Re-election.” He won by a landslide, one that had been cunningly launched a year earlier by a group of aggressive New York/Texas-based U.S. businessmen. As early as December 1875 Diaz had visited New York and New Orleans. In January 1876, he was in Brownsville, Texas, for intensive consultations with the town’s creator, the wealthy and inexhaustibly shrewd New York-born businessman, Charles “Don Carlos” Stillman, and his son James.

On November 21, 1877, General Porfirio Diaz, military hero of Mexico’s liberals, entered Mexico City after opposing one of the nation’s great liberal presidents, Benito Juarez (primarily out of pique), and then (out of political opportunism) Juarez’s much disliked, much less liberal successor, Sebastian Lerdo de Tejado. Diaz immediately called for a new election, flourishing his political (and soon to become ironic) banner: “Effective Suffrage. No Re-election.” He won by a landslide, one that had been cunningly launched a year earlier by a group of aggressive New York/Texas-based U.S. businessmen. As early as December 1875 Diaz had visited New York and New Orleans. In January 1876, he was in Brownsville, Texas, for intensive consultations with the town’s creator, the wealthy and inexhaustibly shrewd New York-born businessman, Charles “Don Carlos” Stillman, and his son James.

Dealing with illiteracy in savvy, secretive ways as a ranch hand, gardener and mountainside handyman, despite the resulting wound to reasoning

- Details

- Published on Friday, 10 August 2012 12:43

- Written by Allyn Hunt

The unrelenting nemesis of journalists and editors is a twined one: Space and time.

Time means deadlines, space dominated by journalism’s commercial engine, advertisements, determines how long a story can be. August 4, a discussion here about the cultural and emotional cost of illiteracy in modern societies, used the eye-opening German novel, and film, “The Reader” — and got its tail cropped by space considerations. This lead some readers to believe that in both novel and film forms, “The Reader” attempts to defend an illiterate woman who became a SS guard during World War II. If that were the case, “The Reader” wouldn’t have found a home here.

‘Piece of My Heart’: Reach-back moments appear in a scattered group of events that recall a Dionysian era that had rough bark

- Details

- Published on Friday, 12 October 2012 13:07

- Written by Allyn Hunt

In an unusual, disconnected flock of days, there seemed to blossom a series of notable small and large events tagged by one observer as “reach-back days.” And it was, to younger people, a long reach – touching the Sixties. For people of a certain age, it was yesterday. Locally, this coincidence of like-minded events was initially noted with the appearance of the Lakeside Little Theatre’s September 19-October 7 performance of “Quartet,” an amusing and touching story of four successful, and now aging, opera singers who unexpectedly come together at a musician’s retirement home in England.

Illiteracy is still a harsh, stunting reality among us, as many mature Mexicans continue to conceal their disadvantage

- Details

- Published on Friday, 03 August 2012 12:27

- Written by Allyn Hunt

Guillermo (Memo) Sanchez was a handsome, rather short, muscular young man who had been carried as an infant on his mother’s back into the mountainside above Jocotepec as she and his father worked the family milpa there. In 1972, a good number of local residents, though they resided in the pueblo of Jocotepec, were still actually cerro Mexicans, living primarily by cultivating and harvesting domestic and wild flora and fauna from the northern mountainsides.

The incarnations of La Dia de Raza, and its creator tried to give birth to a ‘cosmic race,’ a tough dream overwhelmed by incorrigibility

- Details

- Published on Friday, 05 October 2012 11:03

- Written by Allyn Hunt

Mexico, as most people reading this know, is giving Columbus a pass this week, and celebrating El Dia de la Raza, Friday, October 12. Locally, this “day” is overshadowed by the massive celebration of the Virgin of Zapopan. Yet, for a great many Mexican citizens — and long-time foreign Mexico aficionados — who’ve been taught the importance of La Raza, October 12 is a useful time to reflect on the Republic’s splendidly complex and contradictory Day of the Race — which was quickly morphed into Day of the People. Those four words (in Spanish or English) inevitably call up the name of the “father” of this Republic’s modern educational system.

Can the ‘old-guard’ PRI avoid the dinosauric habits that plagued almost all of its 71 years of previous rule under 46-year-old Peña Nieto

- Details

- Published on Friday, 27 July 2012 12:29

- Written by Allyn Hunt

The name of Carlos Salinas de Gortari began showing up in political discussions and news reports even before the social media and mainstream news outlets here confirmed vote purchasing by the once dominant — still powerful — Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) for its candidate, Enrique Peña Nieto. Peña Nieto won the July 1 presidential election with 38.21 percent of the vote, followed by leftist Democratic Revolutionary Part candidate Manuel Lopez Obrador with 31.59 percent. But many voters, even citizens who sold their votes to the PRI, have been protesting Peña Nieto’s “imposed” presidency.

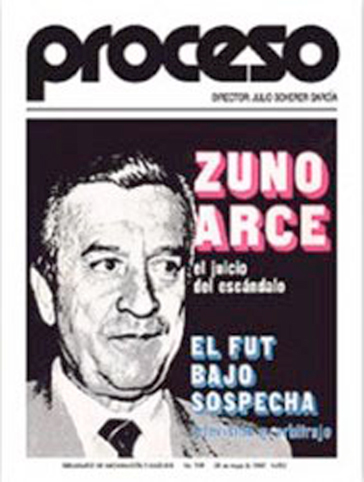

The strange and shameful trial of Ruben Zuno Arce, convicted in the torture and murder of a DEA agent

- Details

- Published on Friday, 28 September 2012 13:34

- Written by Allyn Hunt

Last week a brief story appeared in the United States and Mexican media reporting the September 19 death of Ruben Zuno Arce, brother-in-law of former Mexican President Luis Echeverria Alvarez and son of a former JaIisco Institutional Revolutionary Party governor, Jose Guadalupe Zuno. Zuno Arce was 82 years old and died of lung cancer and cardiovascular disease at the U.S. federal prison in Coleman, Florida.

Last week a brief story appeared in the United States and Mexican media reporting the September 19 death of Ruben Zuno Arce, brother-in-law of former Mexican President Luis Echeverria Alvarez and son of a former JaIisco Institutional Revolutionary Party governor, Jose Guadalupe Zuno. Zuno Arce was 82 years old and died of lung cancer and cardiovascular disease at the U.S. federal prison in Coleman, Florida.

Peña Nieto’s presidency being tagged as a magical mystery tour in dinosaur land, as the shadow of old oligarchs is sensed

- Details

- Published on Friday, 20 July 2012 12:23

- Written by Allyn Hunt

As the victory by Enrique Peña Nieto, presidential candidate of the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI), seemed a much surer thing that it turned out to be, many of Mexico’s political analysts, scholars, former office-holders and veteran news hawks began murmuring the name of former president (1988-1994) Carlos Salinas de Gortari.

Can a plunge into unimaginable turmoil for the GOP be turned around and the damage repaired in just forty-five days?

- Details

- Published on Friday, 21 September 2012 11:58

- Written by GR Staff

A lot of journalists, already set to write a piece on the United States’ two presidential candidates this week, got their boats overturned by life’s habit of swamping such well laid plans. Events — riots and killings in the Middle East, surprising remarks by Mitt Romney — drowned the early patchwork of details journalists begin, almost unconsciously, to mentally bank for such coming stories. And in Mexico, these folk were already fielding rough questions about the tangle muy excéntrico that today passes for a presidential showdown in the U.S.

Political analysts, common citizens warily weigh Peña Nieto’s campaign remarks and the reality facing Mexican culture

- Details

- Published on Friday, 13 July 2012 13:24

- Written by Allyn Hunt

“Tu me conoces” – “You know me” – was what Enrique Peña Nieto kept saying to voters throughout his campaign as presidential candidate for the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI). But despite the thousands of times he said that, out of the thousands of speeches he’s given, Mexicans don’t know him. They became so familiar with the opaque script his handlers and PRI’s dinosauric elders put together for him, that they could repeat it before he did. Even when he changed the simple sequence of the same words.

Figuring out who Miguel Hidalgo was is like combing through a tightly woven web of contradictions and soaring myth

- Details

- Published on Friday, 14 September 2012 13:07

- Written by Allyn Hunt

Both modern Mexico and current “popular” foreign sources have a hard time figuring out who the instigator of Mexico’s great War of Independence, Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla, was. This is not a new problem, but one worsened by a lack of present-day historically well-tuned analysis. The “dusty” pueblo of Dolores (in the intendency of Guanajuato), where the 50-year-old priest was assigned in 1803, has been said by one Hidalgo aficionado to be a “coveted parish.” It brought in a handsome sum – eight-to-nine thousand pesos a year, he contended. Yet the majority of its parishioners were described by contemporary Mexican sources as “illiterate, poor indios,” a description that included the mestizo population also. Hidalgo’s constant efforts to create, and train his parishioners to manage numerous small enterprises were aimed, by all evidence, at improving thin family economies. These included a pottery business, the forbidden production of grapes to produce forbidden wine, planting and nourishing forbidden olive trees to produce forbidden olive oil, beekeeping, a tannery and a silk-making industry, among others.

Both modern Mexico and current “popular” foreign sources have a hard time figuring out who the instigator of Mexico’s great War of Independence, Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla, was. This is not a new problem, but one worsened by a lack of present-day historically well-tuned analysis. The “dusty” pueblo of Dolores (in the intendency of Guanajuato), where the 50-year-old priest was assigned in 1803, has been said by one Hidalgo aficionado to be a “coveted parish.” It brought in a handsome sum – eight-to-nine thousand pesos a year, he contended. Yet the majority of its parishioners were described by contemporary Mexican sources as “illiterate, poor indios,” a description that included the mestizo population also. Hidalgo’s constant efforts to create, and train his parishioners to manage numerous small enterprises were aimed, by all evidence, at improving thin family economies. These included a pottery business, the forbidden production of grapes to produce forbidden wine, planting and nourishing forbidden olive trees to produce forbidden olive oil, beekeeping, a tannery and a silk-making industry, among others.

One Mexican citizen’s unstifled outrage, despite a climate of fear, and amid family warnings to trim an incorrigibly bold nature

- Details

- Published on Friday, 06 July 2012 12:19

- Written by Allyn Hunt

Micaela (“Mica”) Garcia Martinez voted for a candidate whose party she loathed: Josefina Vazquez Mota. She was the first female to run as a presidential candidate for a major Mexican political party. Yet, Mica detests Vazquez Mota’s party, the presently ruling pro-church, pro-business National Action Party (PAN). That’s because she judged the last two local PAN presidentes de municipales to be worse than the normal run of thieves and liars, but, she said bitterly, because they were responsible for deaths of people she knew well. As for the party that “won” last Sunday, the Partido Revolucionario Institucional (PRI), she lived too much of her life under its corrupt and brutal rule, she declared, and wanted nothing to do with that “vile armada”.

Who was Miguel Hidalgo? No one seems to have an answer explaining this fierce, contradictory hero of Mexican independence

- Details

- Published on Friday, 07 September 2012 12:43

- Written by Allyn Hunt

For three weeks rolling displays of the Mexican flags for sale in all sizes and materials have been plying local streets, announcing the September 15-16 national celebration of the beginning of Mexico’s bloody 11-year struggle for independence from Spain. Thousands of people were killed just in the first months of the 1810 uprising. And for the most part, the rebellion was led by disillusioned criollo and mestizo Catholic priests.

Candidates ducking drug war; but then they are being ambiguous about many things such as poverty and education

- Details

- Published on Friday, 29 June 2012 15:32

- Written by Allyn Hunt

One solid, if awkwardly shaped, fact that stands out from the surging national certainty — and its backwash — that Enrique Peña Nieto of the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) will win the presidency Sunday. That fact is that few of those citizens voting for Peña Nieto seem to have any clear, certain idea of what the new president will do with the party shaped by a dictator, General Plutarco Elias Calles, in 1929, as an autocratic instrument of a military/business elite.

Getting a handle on where you are, and what that means. Solving problems here can call for thinking in challenging ways

- Details

- Published on Friday, 31 August 2012 13:08

- Written by Allyn Hunt

In 1995, a campesino named Jose (“Pepe”) Peredo married into the large extended Hernando Diaz family, which was big enough, and generally self-sufficient and insular enough to possess the aura of a clan. He was an unlikely candidate to be accepted by his wife’s many kinfolk because he was both poor and so promiscuous in his personal life that he had two gringo friends. Despite her family’s early skepticism, it was this social adventureness that first attracted the 17-year-old girl who was to become Pepe’s wife. Younger members of the clan were the first generation to become “more broadly socialized,” said a gringo permitted past the rancho’s tree-trunk anchored front gate.

Rainy season begins with a number of of surprises: A woman opens the first furrows of her corn field with drama

- Details

- Published on Friday, 22 June 2012 12:24

- Written by Allyn Hunt

“In this part of Jalisco” — meaning the ample area around Guadalajara/Lake Chapala — “las aguas begin on the day of San Antonio.” That what everyone said when my wife and I arrived in Ajijic in 1963. Though often it didn’t occur quite as promptly as that declaration claimed. But sure enough, the first full-fledged rain arrived this year – with truenos y relampagos (thunder and lightning) — the night of June 12-13, the 13th being the feast day of San Antonio de Padua. And folks out late marking that saint’s day got soaked, as they expected.

Franciscan brothers, the first Catholic order in Mexico, struggled to convert and try to protect Indians set adrift by the conquest

- Details

- Published on Friday, 24 August 2012 12:58

- Written by Allyn Hunt

It is June 24, 1524. Hernan Cortes kneels before twelve ragged and barefooted men, and kisses the soiled, frayed hem of the habit of their leader, Martin de Valencia. At that moment the Spiritual Conquest of Mexico began.

Rainy season saint, martyred in Rome in 120 A.D., his displayed relics venerated by generations of Mexicans, have now disappeared

- Details

- Published on Friday, 15 June 2012 11:05

- Written by Allyn Hunt

For history buffs, for the saint-struck, the fans of religious personages lost in historical mists, for aficionados of religious fecklessness, the ancient saint of rain Saint Primitivo can be enticing.

Grazing horses, crowded highways, fence wreaking storm runoff, missing livestock reckless youngsters and hunting rustlers

- Details

- Published on Friday, 17 August 2012 12:14

- Written by Allyn Hunt

Foreigners and Mexican city folk driving on “secondary highways” between pueblo-sized communities this time of year often complain of horses and cattle grazing on rainy season-born wild grass and weeds along the sides of roadways.

A week of many contradictions, false hopes cunningly planted, Churchly misperception, and a candidate’s face touting adultery

- Details

- Published on Friday, 08 June 2012 10:53

- Written by Allyn Hunt

A week of dizzying contradiction, misdirection, party betrayal by an ex-president, diligently planted false hopes, political handouts, and of course, an immeasurable amount of condescension and poorly veiled contempt for voters. Tawdry stuff from the Catholic Church. Cheery politically designed news from a slew of national, state and municipal candidates all plying voters with money and gifts, while ignoring their more basic needs as inflation surges. But also there was Mexico’s Tourism Department seeking to balance this breathless hype with reality by giving some reassuring statistics: There was a 5.3 percent increase in the number of international visitors to Mexico between January and April. More than half of them were U.S. citizens ignoring their government’s warnings on the increase in crime, and the endless reports of violence.